Opinion: A few beers won't solve racial profiling

Now that the men have drunk their beers and the media frenzy has subsided regarding whether Officer James Crowley was a racist or a good cop, and whether Professor Henry Louis Gates was out of line with his fury or perfectly justified, and whether President Barack Obama handled the whole ordeal well or stupidly, particularly when he suggested Crowley behaved stupidly — now that all of that seems to be settled (or at least has quieted down), there are a few matters that remain unresolved.

A little more than a decade ago, the same incident would not have made national news.

The media wasn't particularly interested in stories of racial profiling, believing those who complained of unfair treatment must have done something to deserve their fate.

But if the media had covered the Gates story back then, and if President Bill Clinton had weighed in, what would have provoked shock and outrage was the president of the United States saying, "What I think we know, separate and apart from this incident, is that there's a long history in this country of African-Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately. That's just a fact."

That comment would have caused a national firestorm because it would have occurred before civil rights organizations had managed to prove with truckloads of data and thousands of personal stories that racial profiling is a fact of life for countless black and brown people in the United States.

One might imagine that widespread acceptance of racial profiling as "a fact" is progress. But imagine if Gates were young, black and poor, and living in San Jose. Would he be better off today than he was a decade ago?

The San Jose Police Department arrests more African-Americans and Latinos per capita than any other city in California. Many of those arrests are "drunk in public" first-time arrests, which are ultimately dismissed. "Arrested and dismissed" sounds like no harm, no foul, right? Wrong.

A mere arrest can result in the denial of employment for jobs like firefighter in some cities in Santa Clara County.

And arrests can — and often do — result in the denial of public housing. An arrest (even if the charges are dropped) equals a record — a life-changing event for young black men in

cities across America.

Because of his race, the young Gates would be more likely to be stopped and searched in the months after his arrest.

And if he is like most teenagers today — of any race — there is a decent chance that one day he'll have some marijuana, alcohol or other contraband.

Police, prosecutors and judges would likely view him as a "repeat offender" — a black kid with a record — and in the blink of an eye, he is a felon.

Suddenly, he may be denied the right to vote in many states and legally discriminated against in employment, housing, education, public benefits and jury service.

He would be relegated to a permanent second-class citizenship.

The prison and jail population has quintupled during the past few decades, and the majority of the increase is due to the mass imprisonment of poor people of color for relatively minor, nonviolent offenses.

Racial profiling is not merely an interpersonal dispute to be settled with a nice chat over some beers. It is the means by which people of color are systematically targeted for mass incarceration.

That conversation will be a long one, and it has barely just begun.

Walter Wilson is a member of the board of directors of the African-American Community Services Agency and a former vice president of the California NAACP. Michelle Alexander, the former director of the Civil Rights Clinic at Stanford Law School, is an associate professor of law at Ohio State University. They wrote this article for the Mercury News.

ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ

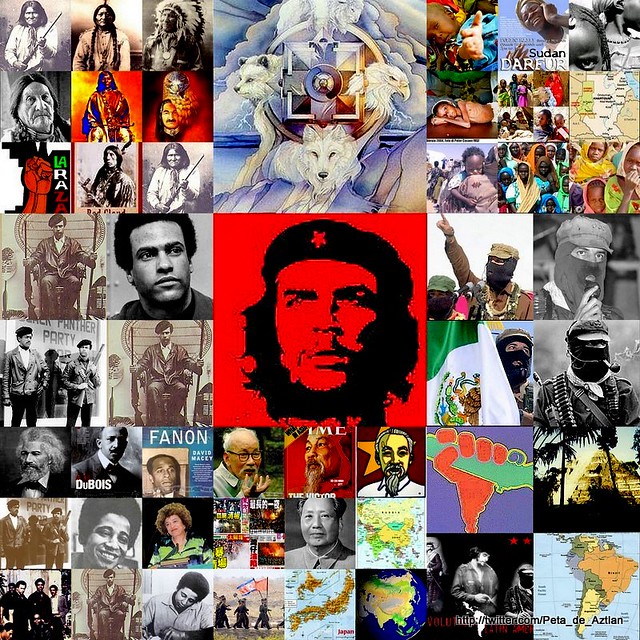

Comment: Racism is so ingrained, build-in and conditioned into the

minds of the typical American psyche that it will take long decades

to filter it out of our collective mentality. One key way to rid us all

of conscious and subconscious racial profiling is for us to work close

together on community projects, break bread together, share meals

and strive for racial-cultural integration at all levels.

Ultimately, there is really only one race of people: the human race!

Comprehend that the usual notion of race is a social fabrication not

proven by DNA. In fact, much of what is seen as racism is actually a

kind of cultural prejudice.

Will you walk by a crowd of young Black youth dressed in ghetto garb

on a corner or cross the street before you come by them? How about

if they have pressed suits and ties on? Are you scared of a group of

Chicanos gathered together on the mall looking around?

Appearances are often illusions. Take time to get to know people before

you label them and rid your soul of foolish fears. Fear your own ignorance

and false assumptions that can spur incorrect actions and motivations.

Education for Liberation! Venceremos Unidos! We Will Win United!

Peter S. Lopez ~aka: Peta

Sacramento, California,Aztlan

Yahoo Email: peter.lopez51@yahoo.com

Links: Join Up!

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Humane-Rights-Agenda/

http://humane-rights-agenda-network.ning.com/

http://humane-rights-agenda.blogspot.com/

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NetworkAztlan_News/

c/s

No comments:

Post a Comment