I Believe Only In The Power Of The People: 22 December, 2005 http://www.countercurrents.org/bolivia-morales221205.htm

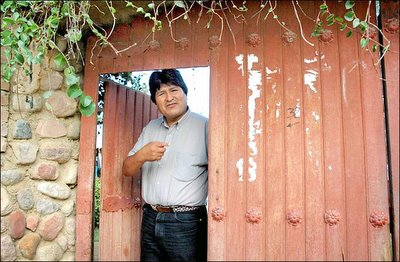

By Che Evo Morales Thank you for the invitation to this great meeting of intellectuals "In Defense of Humanity." Thank you for your applause for the Bolivian people, who have mobilized in these recent days of struggle, drawing on our consciousness and our regarding how to reclaim our natural resources. What happened these past days in Bolivia was a great revolt by those who have been oppressed for more than 500 years. The will of the people was imposed this September and October, and has begun to overcome the empire's cannons. We have lived for so many years through the confrontation of two cultures: the culture of life represented by the indigenous people, and the culture of death represented by West. When we the indigenous people together with the workers and even the businessmen of our country fight for life and justice, the State responds with its "democratic rule of law." What does the "rule of law" mean for indigenous people? For the poor, the marginalized, the excluded, the "rule of law" means the targeted assassinations and collective massacres that we have endured. Not just this September and October, but for many years, in which they have tried to impose policies of hunger and poverty on the Bolivian people. Above all, the "rule of law" means the accusations that we, the Quechuas, Aymaras and Guaranties of Bolivia keep hearing from our governments: that we are narcos, that we are anarchists. This uprising of the Bolivian people has been not only about gas and hydrocarbons, but an intersection of many issues: discrimination, marginalization , and most importantly, the failure of neoliberalism. The cause of all these acts of bloodshed, and for the uprising of the Bolivian people, has a name: neoliberalism. With courage and defiance, we brought down Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada the symbol of neoliberalism in our country on October 17, the Bolivians' day of dignity and identity. We began to bring down the symbol of corruption and the political mafia. And I want to tell you, companeras and companeros, how we have built the consciousness of the Bolivian people from the bottom up. How quickly the Bolivian people have reacted, have said as Subcomandate Marcos says ¡ya basta!, enough policies of hunger and misery. For us, October 17th is the beginning of a new phase of construction. Most importantly, we face the task of ending selfishness and individualism, and creating from the rural campesino and indigenous communities to the urban slums other forms of living, based on solidarity and mutual aid. We must think about how to redistribute the wealth that is concentrated among few hands. This is the great task we Bolivian people face after this great uprising. It has been very important to organize and mobilize ourselves in a way based on transparency, honesty, and control over our own organizations. And it has been important not only to organize but also to unite. Here we are now, united intellectuals in defense of humanity I think we must have not only unity among the social movements, but also that we must coordinate with the intellectual movements. Every gathering, every event of this nature for we labor leaders who come from the social struggle, is a great lesson that allows us to exchange experiences and to keep strengthening our people and our grassroots organizations. Thus, in Bolivia, our social movements, our intellectuals, our workers even those political parties which support the popular struggle joined together to drive out Gonzalo Sánchez Lozada. Sadly, we paid the price with many of our lives, because the empire's arrogance and tyranny continue humiliating the Bolivian people. It must be said, compañeras and compañeros, that we must serve the social and popular movements rather than the transnational corporations. I am new to politics; I had hated it and had been afraid of becoming a career politician. But I realized that politics had once been the science of serving the people, and that getting involved in politics is important if you want to help your people. By getting involved, I mean living for politics, rather than living off of politics. We have coordinated our struggles between the social movements and political parties, with the support of our academic institutions, in a way that has created a greater national consciousness. That is what made it possible for the people to rise up in these recent days. When we speak of the "defense of humanity," as we do at this event, I think that this only happens by eliminating neoliberalism and imperialism. But I think that in this we are not so alone, because we see, every day that anti-imperialist thinking is spreading, especially after Bush's bloody "intervention" policy in Iraq. Our way of organizing and uniting against the system, against the empire's aggression towards our people, is spreading, as are the strategies for creating and strengthening the power of the people. I believe only in the power of the people. That was my experience in my own region, a single province the importance of local power. And now, with all that has happened in Bolivia, I have seen the importance of the power of a whole people, of a whole nation. For those of us who believe it important to defend humanity, the best contribution we can make is to help create that popular power. This happens when we check our personal interests with those of the group. Sometimes, we commit to the social movements in order to win power. We need to be led by the people, not use or manipulate them. We may have differences among our popular leaders and it's true that we have them in Bolivia. But when the people are conscious, when the people know what needs to be done, any difference among the different local leaders ends. We've been making progress in this for a long time, so that our people are finally able to rise up, together. What I want to tell you, compañeras and compañeros what I dream of and what we as leaders from Bolivia dream of is that our task at this moment should be to strengthen anti-imperialist thinking. Some leaders are now talking about how we the intellectuals, the social and political movements can organize a great summit of people like Fidel, Chávez and Lula to say to everyone: "We are here, taking a stand against the aggression of the US imperialism." A summit at which we are joined by compañera Rigoberta Menchú, by other social and labor leaders, great personalities like Pérez Ezquivel. A great summit to say to our people that we are together, united, and defending humanity. We have no other choice, compañeros and compañeras if we want to defend humanity we must change system, and this means overthrowing US imperialism. That is all. Thank you very much. Recorded by Adam Saytanides Translated by Ricardo Sala zzzzzzzzzz Indigenous Leaders Celebrate Morales Victory: 21 December, 2005 http://www.countercurrents.org/bolivia-cevallos211205.htm By Diego Cevallos Iner Press Service MEXICO CITY, Dec (IPS) - The election of indigenous leader Evo Morales as president of Bolivia is being hailed by native leaders from throughout the region as a "sign of hope" for all impoverished and discriminated indigenous peoples in Latin America. Guatemalan Nobel Peace Prize laureate Rigoberto Menchú said that Morales has brought "a refreshing wind" for all aboriginal peoples. For his part, the president of the powerful Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), Luis Macas, said that Morales' victory is a historical landmark unlike anything seen "since the time of Spanish colonialism." Morales, who captured 51 percent of the votes in Sunday's elections according to preliminary results, will take office on Jan. 22 as the first indigenous president in the history of Bolivia, where 60 percent of the population of 8.6 million identify themselves with one of the country's indigenous groups, according to the 2002 census. The 46-year-old president-elect, a member of the Aymara community, Bolivia's largest ethnic group, emerged as a leader of the country's coca farmers in the central region of Chapare, and has consistently spoken out for the struggles and demands of the country's poverty-stricken and marginalised indigenous majority. Menchú, a Mayan Indian activist who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992, said that Morales' triumph was "an important precedent in the social struggles of the entire region," but warned that "we know he is going to need all of the support of his brothers and sisters." Rafael González, chair of the Committee for Campesino Unity (CUC) in Guatemala, told IPS he hopes "Morales' victory will have repercussions throughout the Americas," and that in the future, other indigenous peoples "will have a president who truly represents them, like the one in Bolivia." There are between 33 and 40 million indigenous people in Latin America, divided into some 400 different ethnic groups, although almost all share something in common: poverty and discrimination. Indigenous organisations and leaders, like Morales, Menchú, Macas and González, among others, have been struggling to draw attention to this reality and making ever louder demands for political and social change in their countries since the early 1990s. Over the last 15 years, powerful, organised indigenous movements in Latin America have succeeded in overthrowing governments in Bolivia and Ecuador and forced the issue of aboriginal people's rights onto the political agenda, as in the case of Mexico and the primarily indigenous Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN). Throughout the same period, a growing number of indigenous people have been elected to public office, as mayors, members of Congress and government ministers. In Bolivia itself, Aymara Indian Víctor Hugo Cárdenas served as vice president from 1993 to 1997. Now an indigenous politician has reached the highest seat of power for the first time in Bolivia. Morales "will always be able to count on his indigenous brothers and sisters. If we can counsel or support him in any way, we will do so," said Menchú. The Nobel Prize winner cautioned that the new president will be confronting "a very complicated and complex task, because he will be leading a country where racism and discrimination are very deep-rooted," in addition to "serious economic problems, poverty and social and political divisions." A World Bank report released this year, titled "Indigenous Peoples, Poverty and Human Development in Latin America: 1994-2004", revealed that 74 percent of indigenous people in Bolivia live in poverty. "Almost two-thirds of the indigenous population is among the poorest 50 percent of the population," the researchers reported, noting that "if gains were perfectly distributed, Bolivia's indigenous population would require about twice as much income per person as the non-indigenous population to escape poverty." The indigenous population has 3.7 fewer years of schooling (a total of 5.9 years) than the non-indigenous population (9.6 years) in Bolivia, while the incidence of child labour is nearly four times higher among indigenous than non-indigenous children, the study adds. The World Bank report points out that the political influence of indigenous peoples in Latin America - who account for 10 percent of the population of the region - has "grown remarkably" in the last 15 years, as measured by indigenous political parties and elected representatives, constitutional provisions for indigenous people, and indigenous-tailored health and education policies. Nevertheless, income levels among this group, as well as human development indicators such as education and health conditions, "have consistently lagged behind those of the rest of the population." In the five Latin American countries with the largest indigenous populations - Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru - simply being born indigenous increases the probability of being poor by between 13 and 30 percent. Luis Macas believes that the election of an indigenous president will not only benefit Bolivia, but the rest of Latin America as well. His fellow CONAIE representative Miguel Guatemal, the group's organisational director, said it was especially encouraging that Morales had won the presidential elections within a "neoliberal and colonial" system. "For all of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, Morales' victory is an important precedent that shows there is hope for the future," Guatemal commented to IPS. zzzzzzzzzz Nobelists May Attend Bolivia Inauguration: December 27, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/international/AP-Bolivia-Morales.html LA PAZ, Bolivia (AP) -- A former coca farmer and street protester expects to be surrounded by Nobel laureates, presidents and social activists when he assumes Bolivia's highest office Jan. 22. President-elect Evo Morales is inviting three Nobel Peace Prize laureates -- Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Rigoberta Menchu of Guatemala and Adolfo Perez Esquivel of Argentina -- along with Nobel literature prize winner Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Morales' spokesman Alex Contreras said. The 46-year-old Aymara Indian, who promised during his campaign to be Washington's ''worst nightmare,'' is planning two separate inaugurations -- the official one at the Congress building, followed by one organized as a traditional Indian ritual. Morales, a leftist who has promised to nationalize Bolivia's gas and oil reserves, is scheduled to visit Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva on Jan. 13. The Brazilian financial newspaper Valor said the two will discuss, among other things, Brazil's $1.5 billion investments in Bolivia's gas industry. ''The Brazilian government wants to learn from Morales his real plans for the Bolivian gas,'' the paper said. Morales has also drawn the attention of the American government with his pledges to halt the U.S.-backed campaign to end the growing of coca leaf, which is used to make cocaine. Morales has asked outgoing President Eduardo Rodriguez to also send inauguration invitations to the leaders of the Landless' Movement of Brazil, Indian movements of Ecuador and the leaders of the ''piqueteros,'' a social protest movement of the jobless in Argentina, Contreras said. The outgoing government, meanwhile, said it has invited presidents of a number of countries, especially from Latin America, including Fidel Castro of Cuba and Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, both close friends of Morales. Morales received about 54 percent of the vote in the Dec. 18 election, the highest popular support garnered by any president since democracy was restored two decades ago. zzzzzzzzzz No Left Turn: December 27, 2005 By ÁLVARO VARGAS LLOSA http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/27/opinion/27llosa.html Washington: Forum: Unrest in South America IN 1781, an Aymara Indian, Tupac Katari, led an uprising against Spanish rule in Bolivia and lay siege to La Paz. He was captured and killed by having his limbs tied to four horses that pulled in opposite directions. Before dying, he prophesied, "I will come back as millions." To judge by the overwhelming victory of Evo Morales, an Aymara, in Bolivia's elections on Dec. 18, he kept his promise. Mr. Morales's election has been interpreted as confirmation that South America is moving left. Mr. Morales does not hide his admiration for Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez, and his proposals include the nationalization of the oil industry, the redistribution of some privately owned estates and the decriminalization of coca plantations in the Chapare region. He opposes the Free Trade Area of the Americas and blasts "neoliberalism." It would be a mistake, however, to think that Mr. Morales will become another Hugo Chávez even if that is his wish. The new Bolivian president will not have the resources that Venezuela commands and his popular base is shakier. Moreover, Brazil has an important presence in Bolivia and will be in a position to exercise a moderating influence. Unlike Venezuela, where skyrocketing oil prices brought Mr. Chávez a windfall that allowed him to build a strong social network based on patronage, Bolivia has little revenue. The only reason its fiscal account is not showing a $1 billion deficit is foreign aid, mainly from the United States. Because Mr. Morales's followers toppled the two previous presidents and forced the authorities to impose heavy royalties on multinational companies exploiting natural gas, foreign investment has dried up: only $84 million worth of investment came into the country this year. And the possibility of suddenly turning Bolivia's natural gas reserves (potentially a whopping 52 trillion cubic feet) into an exporting bonanza has been precluded by the cancellation of a project that sought to export natural gas to Mexico and California through Chilean ports. (Bolivia and Chile have been at odds since the late 19th century, when Bolivia lost its access to the sea to Chile in the War of the Pacific.) Bolivia's indigenous population, which wants results quickly, may also hold Mr. Morales in check. His party, Movement Toward Socialism, is a loose amalgam of competing social groups. If Mr. Morales tries to concentrate power, he will need a sturdy, permanent base of support that is by no means guaranteed. Furthermore, the residents of many provinces, especially in the east, are agitating for local autonomy and have warned that they will resist attempts to centralize even more power in La Paz. Bolivia has had left-wing governments before that were toppled by the same people who made them possible. President Carlos Mesa, who replaced Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada in 2003 after violent demonstrations, had the support of the population when he reneged on natural gas contracts with foreign investors and led a virulent campaign against Chile. Yet the masses still turned against him, forcing his resignation in June. Finally, Brazil's pragmatic president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, could also constrain Mr. Morales's ambitions. Brazil is now effectively Bolivia's only foreign investor, and its role is likely to grow even more crucial, because Mr. Morales promises to nationalize the subsoil and keep the high royalties on oil and natural gas exploitation that have kept out investors from other countries. Bolivia therefore will need Petrobras, the Brazilian energy giant, to expand its investments. Mr. da Silva has not been able to rein in Mr. Chávez, but he will have leverage over the more vulnerable Mr. Morales. Of course, whether Mr. Morales will draw closer to Mr. Chávez will in part depend on American policy toward Bolivia. And that, in turn, will depend on whether Mr. Morales decriminalizes coca growing. If he does so, the United States should not overreact, because nothing much will change. Even with the restrictions that are in place now, there are already as many plantations in Chapare as the demand for coca - and Bolivia's capacity to make cocaine from it - warrant. In any case, cocaine production and distribution will still be banned in Bolivia, Mr. Morales says. If Washington were to respond to coca decriminalization by hindering Bolivia's exports of clothing and jewelry to the United States, tens of thousands of families in El Alto, one of Mr. Morales's indigenous power bases, would lose their source of income, and anti-American sentiment would pull Mr. Morales leftward. Thomas Shannon, assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, recently told me that the United States aims to eliminate its remaining protectionist measures (which hamper some South American economies by restricting United States imports of their goods). Few Latin Americans have heard about this endeavor. If the goal is to promote development and foster good relations across the hemisphere, eliminating protectionist policies will be far more effective than making coca plantations the paramount issue in Bolivia-United States relations. Fractious politics and ethnic tensions already make for a delicate situation in the Andes. Let's not make it worse. Álvaro Vargas Llosa, the director of the Center on Global Prosperity at the Independent Institute, is the author of "Liberty for Latin America." zzzzzzzzzz Editorial: A Different Latin America: December 24, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/24/opinion/24sat2.html Bolivia's recent presidential election was almost as history making as Iraq's parliamentary vote. The winner, Evo Morales, will be the first member of the indigenous majority to run Bolivia since the conquistadors arrived nearly five centuries ago. His victory was one of the most decisive since the return of democracy more than two decades ago, ending an era of weak, unstable and ineffective governments. But do not expect any toasts from the Bush administration. During the campaign, Mr. Morales advertised himself as Washington's "nightmare." He opposes almost everything the Bush team stands for in Latin America, from combating coca leaf production to privatizing natural resources and liberalizing trade. His favorite Latin leaders are Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and Fidel Castro of Cuba. And the political popularity of these anti-Washington positions is part of a growing regional trend. The political balance in Latin America has clearly been shifting to the left. Nearly 300 million of South America's 365 million people live under left-wing governments. While many of these governments, like Brazil's and Chile's, have worked hard to cooperate with the United States, others, like Venezuela's, have gone out of their way to bait Washington. Mr. Morales gives every indication of following the Chávez approach. And there could be similar lurches to the demagogic left in the numerous Latin American elections soon coming up in places like Peru, Mexico and Nicaragua. One explanation is that nearly two decades of Washington-recommended economic and trade policies have not done much for millions of urban and rural poor. Another is that the Bush administration has not shown much interest in addressing Latin American social problems. And Mr. Bush has done a terrible job of cultivating personal relationships with Latin American leaders. Few countries adopted Washington's economic prescriptions more eagerly than Bolivia did in the 1980's and 90's. Yet despite considerable mineral and energy resources, it remains South America's poorest country, with 60 percent of its people living in poverty. The left-behind and angry poor voted for Mr. Morales in large numbers, as they have voted repeatedly for Mr. Chávez in Venezuela. When denunciations of Yanqui imperialism in Latin America start coming from the presidential palaces as well as the streets and opposition benches, Washington needs to change its ways. The friendship of neighbors is a terrible thing to lose. zzzzzzzzz U.S. Keeps a Wary Eye on the Next Bolivian President: December 21, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/21/international/americas/21latin.html?fta=y By JOEL BRINKLEY WASHINGTON, Dec. 20 - On the campaign stump, Evo Morales liked to say that if he was elected president of Bolivia, he would become America's nightmare. After his election on Sunday, a State Department official said essentially the same thing, calling Mr. Morales "potentially our worst nightmare." Pix: Evo Morales, the newly elected president of Bolivia, last week in Cochabamba. He has said he will reduce restrictions on coca leaf production. The Bush administration says it fears that Mr. Morales will follow through on his promise to join Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan president, as an anti-American, leftist leader, while also carrying out his promise to reduce restrictions on his nation's production of coca leaf, the primary ingredient of cocaine, much of which finds its way to the United States. Mr. Morales made an early strike on Tuesday when he told Al Jazeera television in an interview that President Bush was "a terrorist" and that American military intervention in Iraq was "state terrorism." The administration's public stance is to wait and see what policies Mr. Morales puts into place. At the State Department briefing on Tuesday morning, Sean McCormack, the spokesman, said the department had congratulated Mr. Morales on his victory and expressed hope for Bolivians that "with this election that they can begin to move beyond what has been a difficult period in Bolivia's political history." "And as for the future, we'll see what kind of policies the next Bolivian president pursues and that the kind of relationship and the quality of the relationship between the United States and Bolivia will depend on what kind of policies they pursue," he said, "including how they govern, do they govern democratically and do they have a respect for democratic institutions." The election could add to a string of difficulties for the Bush administration, which is held in low regard in many Latin American countries. During a visit to the region this fall, Robert B. Zoellick, the deputy secretary of state, described Mr. Chávez and others with similar approaches and policies as "pied pipers of populism." State Department officials say Mr. Morales's campaign speeches appear to place him in that group, assuming he continues the same course in office as he did during the campaign. The officials declined to be identified, citing department policy. Stephen Johnson, a former State Department official and now a senior policy analyst with the Heritage Foundation, said of Mr. Morales, "It will be difficult for him to moderate his position because he has a political base that is a little bit more hard-line, more populist, than he is." That base is Bolivia's indigenous population, from which Mr. Morales came. Many of those people are coca farmers in a region where chewing coca leaf and making coca tea are deeply ingrained in the culture. In Bolivia, though, the election of Mr. Morales on Sunday is seen as a potent signal that the country has tired of the traditional and often corrupt politicians who had long been in power. Saying they were tired of old economic formulas, Bolivians not only elected Mr. Morales but also voted three main parties out of national prominence. Mr. Zoellick and other American officials have been openly critical of Mr. Chávez, a close ally of Mr. Morales's, saying he is eroding democratic freedoms in Venezuela. Mr. Morales has not indicated any intention of doing that. Still, he "has certainly unleashed strong expectations" among his constituents, said Peter DeShazo, another former senior State Department official who now directs the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. "If he is seen as too moderate and accommodating, he risks invoking the wrath of these groups that want radical change." Several State Department officials said the primary challenge that the United States faced in Latin America was the fragility of democratic governments in the region, which makes them vulnerable to populist leaders who, they said, were almost by definition anti-American. Those leaders, the officials said, also tended to chip away at democratic freedoms. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, in an interview with CNN on Monday, said: "The issue for us is, will the new Bolivian government govern democratically? Are they open to cooperation that, in economic terms, will undoubtedly help the Bolivian people, because Bolivia cannot be isolated from the international economy? And so from our point of view, this is a matter of behavior." The State Department office that monitors drug trafficking says Bolivia produces the third-largest coca crop in the hemisphere, behind Colombia and Peru. In a report put out in March, the department said Bolivia exceeded its coca-eradication goals in 2004. Nonetheless, "coca cultivation increased by 6 percent over all." A department official said little had changed since March. During a news conference in La Paz, the capital, on Tuesday, Mr. Morales said that he would not allow unlimited production of coca and that he would hold a referendum to determine how it should be controlled. He promised to fight drug trafficking, but he did not rescind his promise to drop support for the American-financed coca eradication program. The primary focus of that campaign has been to eradicate coca plants in the Chapare region, where Mr. Morales is from. If restraints are lifted, "there is the potential for large-scale industrial production in the Chapare," Mr. DeShazo said. "And that would be of grave concern for the United States." In 2004, the United States spent $150 million on coca-eradication programs in Bolivia, the State Department said. But Bolivia still produced 60,500 acres of coca plant, enough to manufacture 72 tons of cocaine. The Bush administration says, however, that it plans to give Mr. Morales every chance. A senior official is likely to be sent to La Paz to meet and congratulate the new president in the weeks ahead. Juan Forero contributed reporting from La Paz, Bolivia,for this article. zzzzzzzzzz Bolivia's Newly Elected Leader Maps His Socialist Agenda: December 20, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/20/international/americas/20bolivia.html?fta=y By JUAN FORERO LA PAZ, Bolivia, Dec. 19 -After his decisive win in the election for president on Sunday, the Socialist indigenous leader, Evo Morales, vowed Monday to respect private property but repeated his pledge to increase state control over the energy industry and reverse an American-backed crusade against coca, the plant used to make cocaine. Wearing his trademark black jeans and tennis shoes, Mr. Morales arrived in La Paz to begin laying the groundwork for an economic and political transformation that he says will give voice to the poor, indigenous majority that fueled his campaign. "The voice of the people is the voice of God," he said late Sunday. Mr. Morales, 46, a former small-town trumpeter and soccer player who turned a movement of coca farmers into the country's most potent political force, stunned his countrymen on Sunday by burying seven challengers in the most important election since Bolivia's transition from dictatorship to democracy a generation ago. Unofficial results showed that Mr. Morales won up to 52 percent of the vote to become the first Indian president in Bolivia's 180-year history, a victory that solidifies a continent-wide shift of governments to the left. "For the first time a candidate wins with 50 percent plus 1, and it's the biggest margin between the first two finishers," said Gonzalo Chávez, an economist and political analyst at Catholic University in La Paz. "This is a democratic revolution. The voting was tremendously strong, and signifies a tremendous demand for change in Bolivia." President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and President Néstor Kirchner of Argentina, two of the continent's leading left-leaning leaders, quickly offered their congratulations, as did Chile, Spain and the European Union. The United States tried to discredit Mr. Morales in the past by alleging ties to drug trafficking, and ended up increasing his popularity. The administration offered cautious congratulations to Mr. Morales and to the Bolivian people "for carrying out a successful election." But American officials acknowledged that they viewed his presidency with serious concern, while insisting that they would wait to see how he actually governed. A State Department official noted that Bolivia had experienced several years of chaos in government, "and now they have chosen a leader and still have a constitutional process." adding, "We have to respect that, whatever else Morales has said." He declined to be identified, citing department policy. Mr. Morales's party, the Movement Toward Socialism, won nearly half the 27 seats in the Senate and up to half the 130 seats in the lower house. Unofficial figures showed the MAS, as the party is known, also won at least two of nine governorships. Podemos, the party of Jorge Quiroga, a former president, finished a distant second. Three other traditional parties practically disappeared from the national scene. The MAS is now poised to push through legislation tightening the terms on British Gas, Repsol YPF of Spain, Petrobras of Brazil and other foreign energy companies operating here. Mr. Morales has promised to "nationalize" the lucrative natural gas industry, not by expropriating it, but rather by expanding state control over operations, policy and the commercialization of gas. "The government will exercise its right to state ownership of Bolivia's hydrocarbons," he said Monday. Foreign oil companies have in the past said that financially onerous terms could prompt them to cut back on investments, which have fallen from $608 million in 1998 to $200 million last year. But on Monday, Ronald Fessy, spokesman for the Bolivian Hydrocarbon Chamber, said it was too soon to predict. "Governments have to be seen in action, not in times of campaigning," he said. "We hope that this government will work to achieve scenarios that would lead to policies that are good for investments that this industry and Bolivia urgently need." Mr. Morales has also pledged to reverse Bolivia's longstanding alliance with the United States in the generation-long fight against drugs, which has greatly curtailed the coca planting but has set off politically volatile uprisings by coca farmers. Mr. Morales and his followers say much of Bolivia's coca goes for traditional uses, to be chewed or used in tea, while Washington says most of it becomes cocaine. "The fight against drug trafficking is a false pretext for the United States to install military bases," Mr. Morales told reporters on Monday. Even with the mandate from voters, Mr. Morales is not expected to have an easy time in a country rocked by years of social protests fueled by inequality and poverty. He will be under pressure to ensure that the country's budding exports of textiles and furniture continue, while answering to indigenous leaders who seek radical change. Some social movements have vowed to apply pressure. The Bolivian Workers Central, the country's largest labor confederation, said the government would have to expropriate private energy installations from private companies, or face the kind of protests that forced out two presidents since 2003. "He has to make changes or he falls," Jaime Solares, the head of the confederation, said in an interview. In the main square of La Paz, where one president was lynched on a lamppost in 1946, most people seemed tired of protests and wanted to give Mr. Morales a chance . "We have to give him some time," said Martín Bautista, 35, a truck driver. "I feel happy because here a lot of things are about to change." zzzzzzzzzz Coca Advocate Wins Election for President in Bolivia: Published: December 19, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/19/international/americas/19bolivia.html?ex=1135832400&en=906c9cdb3bc281c8&ei=5070 By JUAN FORERO LA PAZ, Bolivia, Dec. 18 - Evo Morales, a candidate for president who has pledged to reverse a campaign financed by the United States to wipe out coca growing, scored a decisive victory in general elections in Bolivia on Sunday. Pix: Evo Morales, 46, a former coca farmer, was mobbed Sunday after winning Bollivia's presidency and receiving up to 51 percent of the vote. Mr. Morales, 46, an Aymara Indian and former coca farmer who also promises to roll back American-prescribed economic changes, had garnered up to 51 percent of the vote, according to televised quick-count polls, which tally a sample of votes at polling places and are considered highly accurate. At 9 p.m., his leading challenger, Jorge Quiroga, 45, an American-educated former president who was trailing by as much as 20 percentage points, admitted defeat in a nationally televised speech. At his party's headquarters in Cochabamba, Mr. Morales said his win signaled that "a new history of Bolivia begins, a history where we search for equality, justice and peace with social justice." "As a people who fight for their country and love their country, we have enormous responsibility to change our history," he said. Mr. Quiroga's concession signaled that he was prepared to step aside and avoid a protracted selection process in Congress, which, under Bolivian law, would choose between the top two finishers if neither obtained at least 50 percent of the vote. "I congratulate Evo Morales," Mr. Quiroga said in a somber speech. The National Electoral Court had not tabulated results on Sunday night, though Mr. Morales echoed the early polls and claimed to have won a majority. His margin of victory appeared to be a resounding win that delivered the kind of mandate two of his predecessors, both of whom were forced to resign, never had. Eduardo Gamarra, a Bolivian-born political analyst from Florida International University in Miami, said Mr. Morales could be on his way to becoming "the president with the most legitimacy since the transition to democracy" from dictatorship a generation ago. A Morales government would become the first indigenous administration in Bolivia's 180-year history and would further consolidate a new leftist trend in South America, where nearly 300 million of the continent's 365 million people live in countries with left-leaning governments. Though most of those governments are politically and economically pragmatic, a Morales administration signals a dramatic shift to the left for a country that has long been ruled by traditional political parties disparaged by many Bolivians. The victory by Mr. Morales will not be welcomed by the Bush administration, which has not hidden its distaste for the charismatic congressman and leader of the country's federation of coca farmers. American officials have warned that his election could be the advent of a destabilizing alliance involving Mr. Morales, Fidel Castro of Cuba and Venezuela's president, Hugo Chávez, who has seemed determined to thwart American objectives in the region. In comments to reporters after casting his vote in the Chapara coca-growing region on Sunday , Mr. Morales said his government would cooperate closely with other "anti-imperialists," referring to Venezuela and Cuba. He said he would welcome cordial relations with the United States, but not "a relationship of submission." He also pledged that under his government his country would have "zero cocaine, zero narco-trafficking but not zero coca," referring to the leaf that is used to make cocaine. Mr. Chávez, who has met frequently with Mr. Morales, expressed confidence that Bolivia would turn a new page with the election. "We are sure what happens today will mean another step in the integration of the South America of our dreams, free and united," he said earlier in the day from Venezuela. The election, which was marked by personal attacks, pitted two fundamentally different visions for how to extricate Bolivia from poverty. While Mr. Quiroga pledged to advance international trade, Mr. Morales promised to squeeze foreign oil companies and ignore the International Monetary Fund's advice. Mr. Morales enjoyed strong support in El Alto, a largely indigenous city adjacent to the capital, La Paz, where voters said they had tired of years of government indifference. "The hope is that he can channel our needs," said Janeth Zenteno, 31, a pharmacist in El Alto. "We have all supported Evo. It is not just what he says. It is that this is his base and he knows us." For Javier Sukojayo, 40, a teacher, the election could signal a transformation of Bolivia into a country where the poor have more say. "It has been 500 years of oppression since the Spanish came here," said Mr. Sukojayo, who counts himself as indigenous. "If we are part of the government - and we are the majority - we can make new laws that are in favor of the majority." zzzzzzzzzz Latin America Looks Leftward Again: December 18, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/18/weekinreview/18forero.html?ex=1135832400&en=948f9392d8156a61&ei=5070 By JUAN FORERO TACAMARA, Bolivia -- AT first glance, there's nothing cutting edge about this isolated highland town of mud-brick homes and cold mountain streams. The way of life is remarkably unchanged from what it was centuries ago. The Aymara Indian villagers have no hot water or telephones, and each day they slog into the fields to shear wool and grow potatoes. But Tacamara and dozens of similar communities across the scrub grass of the Bolivian highlands are at the forefront of a new leftward tide now rising in Latin American politics. Tired of poverty and indifferent governments, villagers here are being urged by some of their more radical leaders to forget the promises of capitalism and install instead a community-based socialism in which products would be bartered. Some leaders even talk of forming an independent Indian state. "What we really need is to transform this country," said Rufo Yanarico, 45, a community leader. "We have to do away with the capitalist system." In the burgeoning cities of China, India and Southeast Asia, that might sound like a hopelessly outdated dream because global capitalism seems to be delivering on its promise to transform those poor societies into richer ones. But here, the appeal of rural socialism is a powerful reminder that much of South America has become disenchanted with the poor track record of similar promises made to Latin America. So the region has begun turning leftward again. That trend figures heavily in a presidential election being held today in Bolivia, in which the frontrunner is Evo Morales, a charismatic Aymara Indian and former coca farmer who promises to decriminalize coca production and roll back market reforms if he wins. Though he leads, he is unlikely to gain a clear majority; if he does not, Bolivia's Congress would decide the race. Still, he is the most fascinating candidate, because he is anything but alone in Latin America. He considers himself a disciple of the region's self-appointed standard-bearer for the left, President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, a populist who has injected the state into the economy, showered the nation's oil profits on government projects aimed at the poor, and antagonized the Bush administration with constant invective. "In recent years, social movements and leftist parties in Latin America have reappeared with a force that has no parallel in the recent history in the region," says a new book on the trend, "The New Left in Latin America," written by a diverse group of academic social scientists from across the Americas. Peru also has a new and growing populist movement, led by a cashiered army officer, Ollanta Humala, who is ideologically close to Mr. Chávez. Argentina's president, Néstor Kirchner, who won office in 2003, announced last week that Argentina would sever all ties with the International Monetary Fund, which he blames for much of the country's long economic decline, by swiftly paying back its $9.9 billion debt to the fund. The leftist movement that has taken hold in Latin America over the last seven years is diverse. Mr. Chávez is its most extreme example. Brazil's president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, by contrast, is a former labor leader who emphasizes poverty reduction but also practices fiscal austerity and gets along with Wall Street. Uruguay has been pragmatic on economic matters, but has had increasingly warm relations with Venezuela. In Mexico, the leftist who is thought to have a good chance to be the next president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has distanced himself from Mr. Chávez. What these leaders share is a strong emphasis on social egalitarianism and a determination to rely less on the approach known as the Washington Consensus, which emphasizes privatization, open markets, fiscal discipline and a follow-the-dollar impulse, and is favored by the I.M.F. and United States officials. "You cannot throw them all in the same bag, but this is understood as a left with much more sensitivity toward the social," said Augusto Ramírez Ocampo, a former Colombian government minister who last year helped write a United Nations report on the state of Latin American democracy. "The people believe these movements can resolve problems, since Latin American countries have seen that the Washington Consensus has not been able to deal with poverty." The Washington Consensus became a force in the 1980's, after a long period in which Latin American governments, many autocratic, experimented with nationalistic economic nostrums like import-substitution and protectionism. These could not deliver sustained growth. The region was left on the edge of economic implosion. With the new policies of the 1980's came a surge toward democracy, a rise of technocrats as leaders and, in the last 20 years, a general acceptance of stringent austerity measures prescribed by the I.M.F. and the World Bank. Country after country was told to make far-reaching changes, from selling off utilities to cutting pension costs. In return, loans and other aid were offered. Growth would be steady, economists in Washington promised, and poverty would decline. But the results were dismal. Poverty rose, rather than fell; inequality remained a curse. Real per capita growth in Latin America since 1980 has barely reached 10 percent, according to an analysis of I.M.F. data by the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research. Meanwhile, many Latin Americans lost faith in traditional political parties that were seen as corrupt vehicles for special interests. That led to uprisings that toppled presidents like Bolivia's Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and Ecuador's Lucio Gutiérrez; it also spawned demagogues who blame free-market policies for everything without offering detailed alternatives. The new populism is perhaps most undefined here in the poorest and most remote corner of South America. Mr. Morales promises to exert greater state control over foreign energy firms and focus on helping micro-businesses and cooperatives. "The state needs to be the central actor," he said in a recent interview. But he is short on details, and that worries some economists. Jeffrey Sachs, a Columbia University development economist and former economic adviser here, says he empathizes with Bolivia's poor and agrees that energy companies should pay higher taxes. But he says Bolivia cannot close itself off to the world. "Protectionism isn't really a viable strategy for a small country," he said. If Mr. Morales does become president, he might well find that the slogans that rang in the streets are not much help in running a poor, troubled country. Mr. da Silva, the Brazilian president, acknowledged as much in comments he made Wednesday in Colombia: The challenge, he said, is "to show if we are capable as politicians to carry out what we, as union leaders, demanded of government." ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Pix: The New Dream Evo Morales, a presidential candidate in Bolivia who promises to roll back free-market reforms, seeks votes in the jungle town of Cobija. Multi-Media> Audio-Slide Show Rise of the Left in Bolivia Forum: Unrest in South America @ Websource: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/18/weekinreview/18forero.html?ex=1135832400&en=948f9392d8156a61&ei=5070 zzzzzzzzzz

No comments:

Post a Comment