http://bit.ly/e2ehik

Man of War: How does Barack Obama differ as a commander in chief from his swaggering predecessor? A lot less than you might think.

Photos from left: Balazs Gardi / basetrack.org (2); Teru Kuwayama / basetrack.org

Photos from left: Balazs Gardi / basetrack.org (2); Teru Kuwayama / basetrack.org

The office of the presidency, once assumed, transforms the outlook of its holder. If the first job of the executive is the protection of the nation's security, the choices presented when the commander in chief must actually sit in the Oval Office and make a decision turn out to be few. The need to pick from among several unappealing ways to defend the nation is what separates presidents from pundits. I believe that much of the virulent hatred directed at President Obama's predecessor, and at Obama himself, arises from a rejection of this proposition. To the hater, the world is simple, not complex. The answers are obvious. "If the president were only as clear-eyed and wise as I am," the protester thinks, "he would see the world as it truly is, and make better decisions." It turns out, however, that in time of war, very different presidents may see the world in roughly the same way.

President Obama, succeeding President George W. Bush, largely adopted Bush's approach to Iraq; decided to use a version of that approach in prosecuting the war in Afghanistan; and widened the terror war beyond the targets pursued by the Bush administration. In the end, the administration even adopted parts of the Bush doctrine. True, Obama cast aside its more idealistic aspect: using American power to build democracy. On the other hand, President Obama has adopted wholeheartedly what we might call the Bush doctrine's political science: the determination to fight our enemies overseas, eliminating them where possible, rather than wait to be attacked.

There is a trope about President Obama, a meme he must set himself to battle: the notion that he cares about domestic policy but has no passion even for a war he insists is a necessity. Middle East expert Fouad Ajami put it this way: "He fights the war with Republican support, but his constituency remains isolationist at heart."

The claim about Obama's constituency may be true—who knows?—but I see no reason to be skeptical of the president's determination to pursue both the Afghan war and the terror war. True, for reasons that are not clear, Obama rarely speaks of victory. This is unfortunate. Wars do have victors, and they do have losers, and if you believe in what you are doing, then it is better to win than to lose. If these are unjust wars, then President Obama should stop prosecuting them, immediately, not at some promised future date. If on the other hand they are just wars, then he should articulate a moral obligation to prevail.

Certainly Obama seems to believe that the obligation exists. Indeed, the president's words and actions suggest very few limits on what he is willing to do to win the wars he seems determined to fight. In this, as many critics have pointed out, Obama seems not too different from Bush. Perhaps what were seen in Bush as character flaws—and what are seen in Obama as surprises—should be counted as neither. Perhaps they are simply the measures a reflective leader might reluctantly take to protect a nation under threat from a new kind of enemy. And if some of these measures—the continued use of prisoner renditions, for example—seem to violate the very theory of just war that the president espouses, the quickest way to end the abuses may be to win.

Most wars wane in popularity as they drag on. A RAND study suggests that the American people tend to support wars as long as America is perceived to be winning. But how is the public to figure out who's winning? I mean this question quite seriously. How many battles of the Iraq War can the reader name? How many from Afghanistan? Out of either ignorance or condescension, the modern news media rarely tell us. One night a year or so after the fall of Baghdad, my wife and I were watching the evening news. The anchor recounted a fierce battle in southern Iraq, and told us how many American soldiers died. Here is what he did not tell us: what piece of ground the battle was contesting, what difference it made who prevailed, and who won. This is not, as the right would have it, some mystical antiwar bias. This is simple ineptitude.

How many Americans today can identify Takur Ghar, one of the bloodiest engagements of the Afghan war? Takur Ghar was a small part of Operation Anaconda, an all-out assault on Al Qaeda forces in March of 2002. The battle was over possession of a mountaintop, a 10,000-foot peak perfect for offensive and defensive military operations.

Here, I think, President Obama could help. We have all seen the passion with which he battles for his vision of what the nation's health-care system should look like, or how the financial sector should be regulated. If he would bring the same determination to rallying the public in support of his wars—yes, his wars now, nobody else's—he would do more than anyone else can to truly support the troops.

Of course, the existence of a consensus does not mean that the consensus is right: both presidents could be wrong. (As on some issues I think they are.) We should be engaged in open and public debate over the morality of what American armed forces are asked to do. We are a nation founded on the notion of dissent, and trying to control what people can say is wrong. On the other hand, at minimum, the existence of a consensus does suggest that some of the more wildly hyperbolic critics of President Bush may owe him an apology. Otherwise, by muting themselves now, they might seem to be playing partisan games with the lives of American service members—and the lives of those we ask them to kill.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

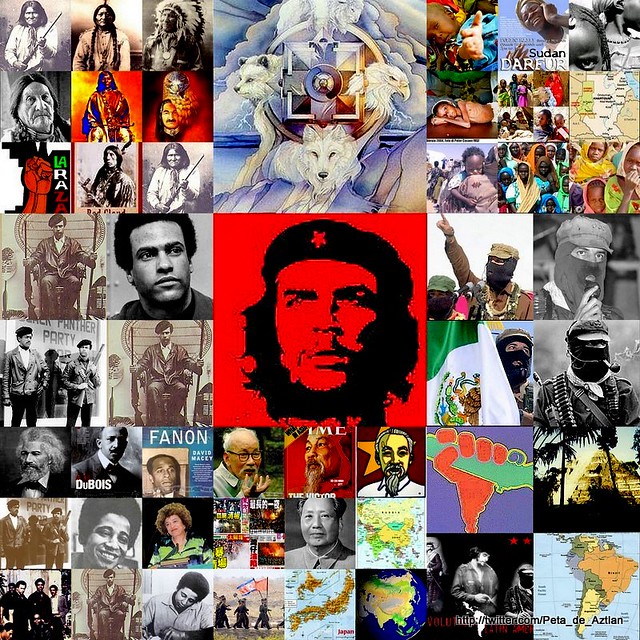

Comment: Kind of a White liberal spin, if not an outright apologist for genocide, but we need to compare the two Presidents. It is true that the magnetism of the Oval Office seems to literally transform its occupant.

Venceremos! We Will Win!

Peta_de_Aztlan

Sacramento, California

Email: peter.lopez51@yahoo.com

http://twitter.com/Peta_de_Aztlan

http://www.facebook.com/Peta51

http://help-matrix.ning.com/

"Those who make peaceful revolution impossible, make violent revolution inevitable." ~ President John F.Kennedy ~ c/s

Man of War: How does Barack Obama differ as a commander in chief from his swaggering predecessor? A lot less than you might think.

Photos from left: Balazs Gardi / basetrack.org (2); Teru Kuwayama / basetrack.org

Photos from left: Balazs Gardi / basetrack.org (2); Teru Kuwayama / basetrack.orgThe election of Barack Obama, according to critics and admirers alike, ushered in a new era in American foreign policy. Perhaps. But it did not usher in a new era in American warfare. Under Obama, we fight in much the same way that we did under his predecessor—for similar reasons, with similar justifications. Strip away the soaring rhetoric and you begin to discover what probably we should have known from the start: when it comes to war, presidents do what they think they must.

Obama might have run in 2008 as the peace candidate, but next time around he will be running as a war president. This simple truth cannot be avoided. Although the next presidential election will doubtless feature bitter disputes over domestic policy, it will also be a referendum on Obama as commander in chief of the mightiest armed forces on the face of the globe.

Surely a degree of Barack Obama's electoral victory was due to his successful effort to persuade voters that he was a builder of bridges. It even looks as if he has; not in domestic policy, which remains as polarized as ever, but in his approach to war. True, there were people on the left and right alike who thought that America had elected an antiwar president, but that simply turned out not to be true. Rather, the nation elected a president in the tradition of American wartime leaders: a man ultimately willing, whether or not it was his original intention, to sacrifice idealism for pragmatism in pursuit of his primary duty of keeping the nation safe.

The office of the presidency, once assumed, transforms the outlook of its holder. If the first job of the executive is the protection of the nation's security, the choices presented when the commander in chief must actually sit in the Oval Office and make a decision turn out to be few. The need to pick from among several unappealing ways to defend the nation is what separates presidents from pundits. I believe that much of the virulent hatred directed at President Obama's predecessor, and at Obama himself, arises from a rejection of this proposition. To the hater, the world is simple, not complex. The answers are obvious. "If the president were only as clear-eyed and wise as I am," the protester thinks, "he would see the world as it truly is, and make better decisions." It turns out, however, that in time of war, very different presidents may see the world in roughly the same way.

President Obama, succeeding President George W. Bush, largely adopted Bush's approach to Iraq; decided to use a version of that approach in prosecuting the war in Afghanistan; and widened the terror war beyond the targets pursued by the Bush administration. In the end, the administration even adopted parts of the Bush doctrine. True, Obama cast aside its more idealistic aspect: using American power to build democracy. On the other hand, President Obama has adopted wholeheartedly what we might call the Bush doctrine's political science: the determination to fight our enemies overseas, eliminating them where possible, rather than wait to be attacked.

There is a trope about President Obama, a meme he must set himself to battle: the notion that he cares about domestic policy but has no passion even for a war he insists is a necessity. Middle East expert Fouad Ajami put it this way: "He fights the war with Republican support, but his constituency remains isolationist at heart."

The claim about Obama's constituency may be true—who knows?—but I see no reason to be skeptical of the president's determination to pursue both the Afghan war and the terror war. True, for reasons that are not clear, Obama rarely speaks of victory. This is unfortunate. Wars do have victors, and they do have losers, and if you believe in what you are doing, then it is better to win than to lose. If these are unjust wars, then President Obama should stop prosecuting them, immediately, not at some promised future date. If on the other hand they are just wars, then he should articulate a moral obligation to prevail.

Certainly Obama seems to believe that the obligation exists. Indeed, the president's words and actions suggest very few limits on what he is willing to do to win the wars he seems determined to fight. In this, as many critics have pointed out, Obama seems not too different from Bush. Perhaps what were seen in Bush as character flaws—and what are seen in Obama as surprises—should be counted as neither. Perhaps they are simply the measures a reflective leader might reluctantly take to protect a nation under threat from a new kind of enemy. And if some of these measures—the continued use of prisoner renditions, for example—seem to violate the very theory of just war that the president espouses, the quickest way to end the abuses may be to win.

Most wars wane in popularity as they drag on. A RAND study suggests that the American people tend to support wars as long as America is perceived to be winning. But how is the public to figure out who's winning? I mean this question quite seriously. How many battles of the Iraq War can the reader name? How many from Afghanistan? Out of either ignorance or condescension, the modern news media rarely tell us. One night a year or so after the fall of Baghdad, my wife and I were watching the evening news. The anchor recounted a fierce battle in southern Iraq, and told us how many American soldiers died. Here is what he did not tell us: what piece of ground the battle was contesting, what difference it made who prevailed, and who won. This is not, as the right would have it, some mystical antiwar bias. This is simple ineptitude.

How many Americans today can identify Takur Ghar, one of the bloodiest engagements of the Afghan war? Takur Ghar was a small part of Operation Anaconda, an all-out assault on Al Qaeda forces in March of 2002. The battle was over possession of a mountaintop, a 10,000-foot peak perfect for offensive and defensive military operations.

In the end, Anaconda was a mixed success. Military analysts learned a good deal from what went wrong. In the Vietnam era, the public often participated in such debates, because we received blow-by-blow accounts from the battlefield. Many opponents of the war, back then, took pride in following its progress, the better to dissect it. Today is different. Some in the press tried to cover Anaconda, but America seemed to pay little attention. Somehow Anaconda, like the other important engagements of Iraq and Afghanistan, has dropped off the radar. We manage to pronounce upon the war without troubling to understand it.

Here, I think, President Obama could help. We have all seen the passion with which he battles for his vision of what the nation's health-care system should look like, or how the financial sector should be regulated. If he would bring the same determination to rallying the public in support of his wars—yes, his wars now, nobody else's—he would do more than anyone else can to truly support the troops.

Although President Obama has spoken of the possibility of using military force for humanitarian purposes, he considers defense of the nation his highest duty, and there are few Americans who would disagree. The manner in which he interprets this mandate turns out to be little different from the interpretation offered by President Bush. President Obama has even contended for means that Bush did not—the right to assassinate American citizens, for instance—and seems to have greatly increased the use of everything from remote missile strikes to secret military operations. The sharp debate over the ways in which Obama has supposedly unraveled Bush policies is, as one observer noted, "mostly window dressing for just what was going on before." On matters of the nation's security, at least, the Oval Office evidently changes the outlook of its occupant far more than the reverse.

Of course, the existence of a consensus does not mean that the consensus is right: both presidents could be wrong. (As on some issues I think they are.) We should be engaged in open and public debate over the morality of what American armed forces are asked to do. We are a nation founded on the notion of dissent, and trying to control what people can say is wrong. On the other hand, at minimum, the existence of a consensus does suggest that some of the more wildly hyperbolic critics of President Bush may owe him an apology. Otherwise, by muting themselves now, they might seem to be playing partisan games with the lives of American service members—and the lives of those we ask them to kill.

Comment: Kind of a White liberal spin, if not an outright apologist for genocide, but we need to compare the two Presidents. It is true that the magnetism of the Oval Office seems to literally transform its occupant.

Venceremos! We Will Win!

Peta_de_Aztlan

Sacramento, California

Email: peter.lopez51@yahoo.com

http://twitter.com/Peta_de_Aztlan

http://www.facebook.com/Peta51

http://help-matrix.ning.com/

"Those who make peaceful revolution impossible, make violent revolution inevitable." ~ President John F.Kennedy ~ c/s

No comments:

Post a Comment