The birth of Latin American identity

Writer Rubén Martínez and filmmaker Carl Byker take a revisionist look at the dramatic encounter between the Old World and the New World in "When Worlds Collide," debuting Monday on PBS stations.

Emmy-winning Journalist Ruben Martinez is the host of the PBS special "When Worlds Collide." (Mariah Tauger, Los Angeles Times / September 27, 2010) |

As he stood beside the ornate tomb in Seville's massive cathedral in southern Spain, Rubén Martínez didn't know whether to curse or bless the man whose bones lie there.

"It's kind of like that classic mestizo dilemma," Martínez said, using the traditional term denoting people of mixed European and indigenous American ancestry. "He's my dad. I'm a bastard kid. I hate him, I love him."

Not every American harbors such complex, passionate feelings for Christopher Columbus: intrepid explorer, opportunistic slave trader, problematic New World progenitor.

But Martínez, an Emmy Award-winning journalist, author, musician and literature professor at Loyola Marymount University, who was raised in Los Angeles as the son of Salvadoran-Mexican immigrants, believes those conflicted emotions are part of what it means to be the offspring of different, sometimes warring cultures.

Martínez and filmmaker Carl Byker dig deep into the origins of Latin American identity, and the societies it shaped, in "When Worlds Collide," a 90-minute documentary that will premiere at 9 p.m. Monday on PBS channels across the country, including KCET in Los Angeles. A rich, revisionist look at the dramatic encounter between Spain's colonizers and the Western Hemisphere's indigenous peoples, as well as the African slaves brought to work in the New World, "When Worlds Collide" explores how contact changed those civilizations forever, both for better and worse.

"People think of it as the Conquest," said Byker, an Echo Park resident whose previous films include "Andrew Jackson: Good, Evil and the Presidency." "That's been the conquerors' spin. What's really gone on is that there's been an ongoing negotiation between the two sides, and it's still going on."

For Martínez, the program's host and co-writer with Byker, making "When Worlds Collide" was a moving, often surprising journey of personal as well as historical discovery.

As a child visiting relatives in San Salvador, he said, he'd been exposed to the Old World's architectural and other legacies, and always felt "at home" in that environment. But as a historian and writer-researcher who has spent many years living and working in Mexico and Central America, he's keenly aware that imperial Spain's sumptuous façade was built with the brutally exploited labor of indigenous Americans and black slaves.

Visiting Spain for the first time to shoot "When Worlds Collide" brought those thoughts and feelings to the surface. "I just kept having these déjà vu moments of recognition," Martínez said during an interview last week at Antigua Coffee House in Cypress Park, not far from his home.

The documentary opens at Echo Park Lake, near downtown Los Angeles, with a tracking shot of Martínez pushing his fraternal twin daughters in a stroller. As he walks, he wonders aloud how to describe his children's ethnicity, given his own heritage and that of his Mexican-Native American-Greek wife.

Martínez, who grew up in Silver Lake and graduated from John Marshall High School, said that for most Latin Americans and Latinos the concept of mestizaje — the blending of two or more cultures to produce a third — is so fundamental a part of identity as to be "like breathing." But he expects the term will be unfamiliar to many non-Latino viewers tuning in to the program in places such as Nebraska.

From today's Echo Park, "When Worlds Collide" moves swiftly across time and space to consider how mestizaje reshaped everything from religious beliefs and architectural styles to skin tones and culinary tastes both in Spain and its overseas territories. Visiting such locales as a market in the heavily indigenous southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, the fabulously lucrative Cerro de Potosí silver mine in Bolivia and the ancient Incan city of Machu Picchu in the Peruvian Andes, Martínez chats with locals while recounting a complex historical exchange in authoritative, jargon-free language.

The film then crosses the Atlantic to Roman Catholic Spain, which in the 1490s was advancing in another bitter struggle between contentious cultures: the expulsion of the Islamic Moors from the Iberian Peninsula.

USC associate professor of history María Elena Martínez (no relation to Rubén), who served as the documentary's principal academic consultant, said the filmmakers' use of mestizaje was a powerful leitmotif. While she has cautioned in her writings that concepts of ethnic "mixing" can be as misleadingly dangerous as those of ethnic "purity," Martínez said that mestizaje can help expand cultural dialogue in the United States beyond the "binary black and white" ethnic terms that are "so dominant."

Just as significant, Rubén Martínez said, the idea of 16th century cultural mixing reminds us that those exchanges continue now, especially in places like his hometown.

"What percentage of indigenous languages survived up until today? A great many were lost," he said. "But if you go to a Oaxacan marketplace — hell, go to El Mercado on 1st Street, take the Gold Line — and a lot of indigenous languages are being spoken."

reed.johnson@latimes.com

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

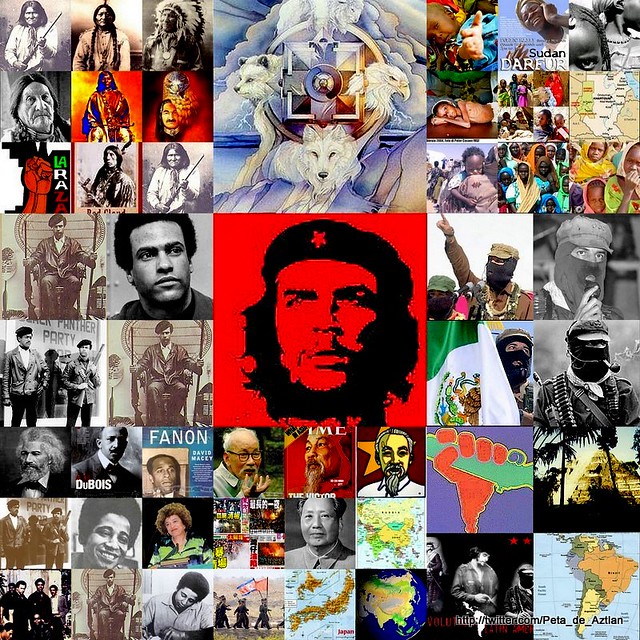

Unidos Venceremos! United We Will Win!

PETER S. LOPEZ AKA: Peta-de-Aztlan

Sacramento, California

Email: peter.lopez51@yahoo.com

http://twitter.com/Peta_de_Aztlan

http://www.facebook.com/Peta51

http://help-matrix.ning.com/

"An invasion of armies can be resisted, but not an idea whose time has come."

~ Victor Hugo

c/s

No comments:

Post a Comment