California prison behavior units aim to control troublesome inmates

cpiller@sacbee.com

Published Monday, May. 10, 2010

Second of two parts

Standing over a small metal sink, a prisoner pours water over his head and face. It's usually the only way to bathe, and offers a brief respite from staring at barren, pockmarked walls in a tiny cell.

Such is daily life inside the behavior unit at the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison in Corcoran, said Tally Molina, an inmate allowed out of his cell once every third day for a quick shower.

Asked how he occupies his time, Molina spoke of meals and some reading, but added: "Nothing really breaks the monotony."

Behavior units were created in six California prisons as a middle ground between the general prison population and security housing that inmates call "the hole." The behavior units were designed for troublemakers or those who reject cellmates. Since their inception in 2005, well over 1,500 inmates have passed through behavior units, where reduced privileges are supposed to be combined with "life skills" classes.

A Bee investigation found that the units are marked by extreme isolation and deprivation. Most of the classes were halted by budget cuts. Some inmates endure lives devoid of exercise, social interaction, even time outside of the cell – for months on end. In interviews, many seemed confused about the purpose of the units and desperate about their future.

Scott Kernan, undersecretary for operations in the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, conceded that an absence of classes "leads to increased inmate idleness and might ultimately have the opposite effect of what … was intended" – that is, the units might provoke the disruptive behavior they were designed to curb.

Perpetual lockdowns

Inside the activity room in the behavior unit in Corcoran, Capt. Felix Vasquez proudly pointed out pristine educational materials carefully arranged on a table.

Titles such as "Cage Your Rage" and "Beat the Street" are designed to help recalcitrant inmates turn a corner on violence. They are the active ingredient in what officials described as a program with excellent results: About 80 percent of its participants eventually return to the general prison population.

Yet, in interviews with Corcoran prisoners it gradually became clear that not one had taken so much as a single class. None had seen, let alone cracked open, a single book.

Instead, the unit was "locked down" nearly 24 hours a day. No classes, no exercise yard, no distractions.

Latino prisoners had barely been out of their cells for nine months, following a fight unrelated to the behavior unit. Lockdowns are frequent at other such units, and throughout the prison system.

Inmates pressed forward to peer out of narrow windows from 6-foot-by-12-foot cells, with their scarred bunks, colorless surfaces and metal toilets. A heavily armed guard, posted in a central tower, scanned the cavernous cellblock for any hint of trouble.

Asked about the curriculum he and other officials had trumpeted, Vasquez conceded that coursework has become more aspiration than reality.

The term "behavior modification" has a controversial past. From the 1950s to the 1970s, behavior modification scientists subjected inmates to sensory-deprivation, pharmaceutical, electroshock and surgical experiments meant to restrain criminal impulses. Some of the tests were conducted at the California Medical Facility prison in Vacaville.

But the new prison behavior modification units were supposed to be different and, in 2008, were renamed "behavior management units," partly to distinguish them from those notorious labs and emphasize a more humane approach, featuring self-improvement.

Yet, at Salinas Valley State Prison, behavior-unit inmate Kevin Hunt sued after he was kept indoors and deprived of exercise for five months – in contrast to his term in the hole, where he enjoyed regular time in the exercise yard. Last year, a judge deemed that lack of outdoor access unconstitutional and ordered officials to provide yard time of at least five hours a week. But his order doesn't apply during lockdowns.

"You don't have anything to get your senses up. Like in the (hole) you at least have a TV or a radio," said Tony Curtis, a Corcoran inmate in his third month in the locked down behavior unit. "In a normal program, doing school, or doing a job assignment, you would have something positive to keep you out of trouble. … (Here) you don't have nothing to look forward to."

Sticks and carrots

Initially, modifying behavior was thought to require both sticks and carrots. Sticks included lost exercise yard time, reduced canteen privileges, fewer family visits and confiscation of inmate-owned TVs. Carrots, for inmates who behaved and finished classes, were increased privileges and, ultimately, "graduation" back to normal cellblocks.

Terrell Wright is one such graduate. Spectacles and a calm demeanor belie a youth of gangs, drugs and violence in Los Angeles that landed Wright in prison.

The author of two memoirs, Wright, 40, apparently ignored his own life lessons. In 2008 he tried to get another inmate to assault an enemy. After a stint in the hole, Wright found himself in the behavior unit.

He credited classes there with turning him around. Now a prison clerk, well-regarded by officials, Wright seems to embody the promise of behavior modification: a problem inmate who becomes a model prison citizen.

Vasquez praised Wright and lamented the lack of classes at Corcoran today. But he was not unduly concerned. Inmates who return to the general population, he said, succeed at about the same rate with or without life skills lessons. Fear of deprivation alone, he said, is a powerful motivator.

"Any tool that we have for behavioral control – we're going to utilize it," agreed Lt. Shawn Mclinn, a spokesman for Calipatria State Prison east of San Diego. "It keeps the staff safe, it keeps the inmates safe."

The opposite may be true when it comes to behavior units.

When The Bee toured the unit in Calipatria in March, officials there said inmates often bounced back and forth between the hole, the behavior unit and the general population.

At High Desert State Prison in Susanville – subject of a Bee article Sunday about alleged prisoner abuse – half of behavior unit inmates failed outright.

A state research report on the High Desert unit, recently released after being withheld by prison officials for nearly two years, said extreme deprivation had earned that unit a reputation for being harsher than the hole. In interviews with The Bee, many inmates said the same was true across the prison system.

Inmates at High Desert told state researchers that they would act out to be placed in the hole instead of the behavior unit. "If there is any truth to this assertion," the researchers noted, the "program could potentially lead to more violent behavior."

"Deprivation in these settings should be a matter of necessity, not of choice," said Joel Dvoskin, a correctional psychologist at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. "If it's so restricted that people get worse, more violent, more angry, then it becomes counterproductive."

The behavior units were sold to lawmakers as a way to reduce recidivism. But the corrections department researchers who evaluated High Desert pointed out that with an emphasis on punishment, such units likely would lead to more crime in the community and more convicts returning to prison.

"This program is not going to help us – our behavior – because they keep us in the cell all day," said Robert Lane, housed in the Calipatria behavior unit for the past year. "They don't give us no recreation, they don't give us no day room. We don't get no phone calls. We can't talk to our family. So we building up more and more anger."

ONLINE

If you missed part one of this special report Sunday, read it online, where you also can hear inmates describe alleged abuse and see a gallery of prison images:

sacbee.com/

investigations

© Copyright The Sacramento Bee. All rights reserved.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

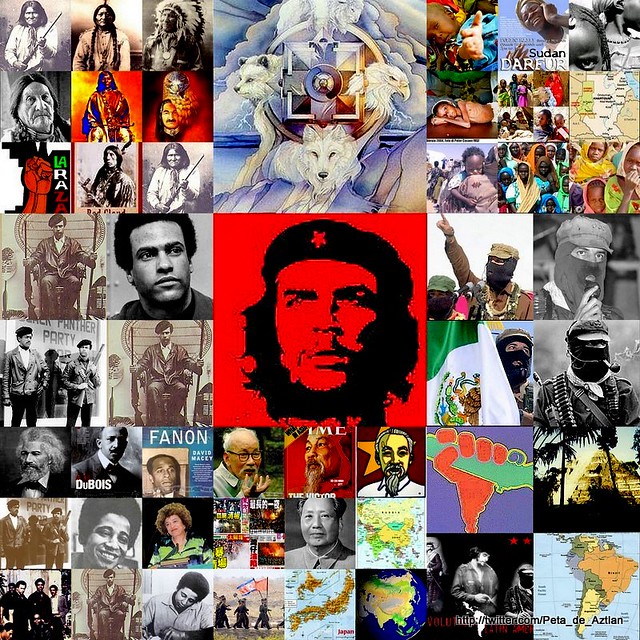

Unidos Venceremos! United We Will Win!

~Peta-de-Aztlan~ Sacramento, California, Amerika

Email: peter.lopez51@yahoo.com

http://help-matrix.ning.com/

http://twitter.com/Peta_de_Aztlan

http://www.facebook.com/Peta51

"Those who make peaceful revolution impossible,

make violent revolution inevitable."

~ President John F.Kennedy ~ Killed November 22, 1963

c/s

No comments:

Post a Comment